Project Space Festival Day 15: Radical Praxes

nationalmuseum is a large white space on the fourth level of an old factory. And yet it is also not a classic white cube, because the space’s aesthetic is, even if discretely, loaded with history. This is not a neutral place, and so ample space is opened for the generation of new ideas.

In the exhibition A Political Idiom, Radical Praxes fills the entire space not so much with a soberly installed objects as with a very specific intensity.

Two large works set up opposite one another frame the length of the space. On one end, a black-and-white image plasters almost the entire wall. This work, by Ella Ziegler, shows Japanese women fighting one another: a frame from the artist’s film drawing on a book form the 1950s about fighting. Deformed by its enlargement, the strong monochrome contrasts afford this image of close struggle a particular stridency. This tension is also maintained in the other exhibited works.

Filling the wall of the opposite end of the space, the video-work and manifesto of Matthew Burbidge, RP01a, consists of a series of images from art institutions, finance and institutions of power. The video formulates an appeal to break out of the lethargy in which the system cradles us.

In the center of the space, a table bears a screen showing a video work, beside hewed blocks of iron and a form of mining pick. This constellation by Tee Byford thematizes industrial big business and their massive under-appreciation of the environment as well as of human labour-power, using a formal language that convinces through its simplicity.

A Political Idiom is an exhibition that highlights, with a minimum of artifice, the artworks and their contents. The dialogue between works together with their concrete spatial arrangement express the radical praxis that this collective has prescribed for itself.

A Political Idiom, installation view, Radical Praxes, Project Space Festival Day 15

A Political Idiom, installation view, Radical Praxes, Project Space Festival Day 15

Photo: Joanna Kosowska

Project Space Festival Day 16: TOKONOMA

It was already dark when I found TOKONOMA. On the periphery of west Berlin, between two bypasses, under the bridge of an autobahn and isolated by the golden glow of a streetlamp: a van, a group of people, soup, beer, and some other, less visible elements that later became apparent.

TOKONOMA is a project space from Kassel run by students of the Kunsthochschule there. Based in a former beauty salon, the space hosts a broad format of events, bringing together club culture, young art and conversation. In Japanese, tokonoma refers to the tradition of displaying small objects in the home as an initiation for conversation among guests. Uprooted to Berlin for the Project Space Festival, TOKONOMA used this situation to prompt more general questions about what home might be in their presentation, entitled Home Coming Parade (with Nile Koetting, Sofia Stevi (Fokidos), Mieko Suzuki und Yukihiro Taguchi). Does home still exist? What do we do when that which we secretly hoped for seems to have disappeared?

I associated this question immediately with Marc Auge’s „non-places“ – ubiquitous sites peculiar to the fractured spaces generated by global capitalism, such as shopping malls or carparks. And indeed the site under the autobahn could be one such place – but if so, several different realities were brought into syncronization under the bridge. Stop-motion animations by Yukihiro Taguchi showed us objects with tactics that made themselves at home anywhere – polystyrene blocks hugging pillars and occupying park benches, piles of rubbish flowing into new constellations and then collapsing again. These films were themselves projected onto a round concrete bollard supporting the bridge, the image distorted by its infrastructure, making itself at home. I discovered a less visible infrastructure when I turned on my smartphone, only to realize it was hooked up to an open network with a name that was constantly changing: a hidden poem. In the van, a small tablet on a top shelf revealed a young man sitting at a control panel in front of a digital visualization in which a satellite navigates the atmosphere, the earth rotating below. Zoom in, zoom out, zoom in again: upon opening the web browser of my phone, I was automatically redirected to a site hosting a text describing the mellow warm sunshine and smells of a specific house filled with the comings and goings of artists, poets and philosophers – somewhere in Athens, somewhere warmer. The text concluded with an invitation to visit this faraway home, and a contact email address to the artist, Sofia Stevi (Fokidos). In this dark non-place on the peripheries of Berlin, surrounded by cars and friends, strangers and acquaintances of the art world, the intimate space of my phone was suddenly a portal promising another, brighter home. One strategy for dealing with the temporary flow of things is to believe in the promise of stability elsewhere.

Home Coming Parade, installation view, TOKONOMA Project Space Festival Day 16

Home Coming Parade, installation view, TOKONOMA Project Space Festival Day 16

Project Space Festival Day 17: KN Raum fuer Kunst im Kontext

Through a thicket of layered thick plants there is the bright night sky filled with flocks of snow or stars. Growing plants rustle in the wind, and so might the paper cut-outs in Katie Armstrong’s This is where (2016) – my entry-point into Know The Ways, a group exhibition and collaboration that negotiated the mystery of the world across a variety of media, bringing to life a mysticism that might be medieval or modern.

KN is primarily a shared working space, but over the month of August, members of the KN collective Katie Armstrong, Carleen Coulter, Kika Jonsson, Vivian Kvitka, Jana Nowack and Emily Zuch drew inspiration on the life work of Hildegard von Bingen (*1098). Hildegard lived in a world in which spirituality and science were entirely intertwined. The KN collective asked itself how, in the contemporary era, a medieval sense of the mysterious might have survived or indeed been reinvented?

As a tenth-born child, Hildegard von Bingen was tithed to the church and raised by an anchoress near the Disibodenberg monastery. Women came together here and a convent formed, for which she later became the abbess. As a woman who experienced dazzling spiritual visions, she wrote philosophical and scientific texts, composed countless liturgies, and was a highly sought-for advisor to medieval courts and the religious order.

In her drawing Alps #3 (2016), Kika Jonsson’s spare, careful graphic language cast an analytic gaze towards the sublime. Vivian Kvitka’s Pipefish (2016), although a digitally rendered print, channeled a darker, more sentimental response to the „quick and wet“ dark shallows of poet Mary Oliver’s (*1935) work of the same title. Jana Nowack’s The Poodle Egg (2016), two glossy digital prints of primordial and hypercoloured eggs or planets in metamorphosis, mirrored flashes from a live cam of raptors‘ nests cut with imagery of the earth viewed from an aeroplane (Untitled 2016, Carleen Coulter). Emily Zuch’s Near Sight Far Sight (2016), an animation of shape-shifting plants accompanied by music by Scott Mannion, could be viewed only by looking down an upside-down plinth.

Alongside an hour-long session in Alexander Technique movement therapy by Winston Chmielinski with practitioner Susanne Feld, KN presented a live performance of Sacred Harp music in the exhibition space. Sacred Harp is a tradition of polyphonic participatory singing that emerged in churches of the American South in the early 19th century. Facing inward, sacred harp singers perform only for themselves, leaving no official space for an audience. Hildegard von Bingen reportedly invented a language in order to come closer to the heavens. The hermetic worlds of each of these works, with some random and some clear lines of connection, offer glimpses into other invented languages.

Performance by Sacred Harp Berlin at KN, Project Space Festival Day 16

Performance by Sacred Harp Berlin at KN, Project Space Festival Day 16

Photo: Joanna Kosowska

Project Space Festival Day 18: alphanova & galerie futura

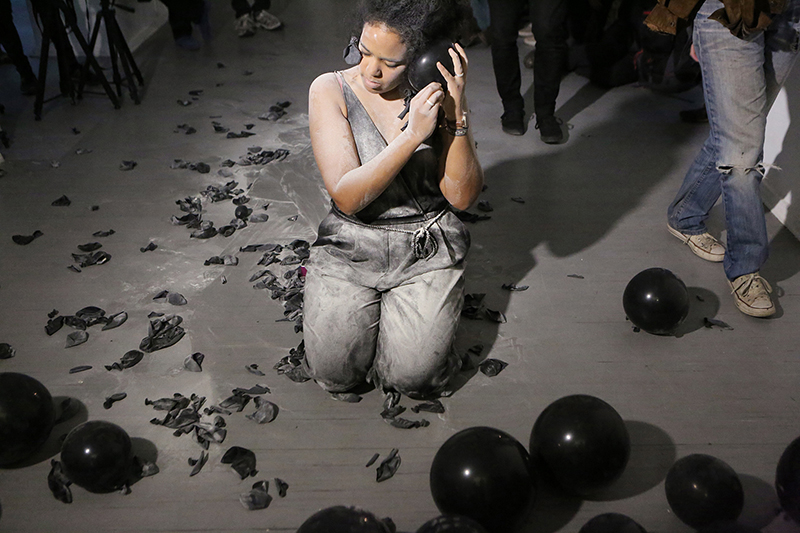

Just over a century ago, south of Berlin in Brandenburg, around 30,000 prisoners of war – Muslim Arabs, Indians and North Africans – from the British and French armies were held captive. The Ottoman Empire, at that time a German ally, had made a call for Holy War against British and French colonial powers, and German forces integrated the Jihad into their policy. The intention was to encourage Muslim prisoners to practice their religion in the hope that they might sever their allegiance to France and Britain in favor of the German/Ottoman alliance. A 23-metre-high mosque was built onsite, while inmates were encouraged to participate in Ramadan. German ethnographers took advantage of this „practical opportunity“, treating the camp like a living museum. The resulting sound recordings form an archive which Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro drew on in her performance If You Fail To Cross The Rubicon, asking: where are the women’s voices in these recordings?

The entrance to the project space in Kunstquatier Bethanien, which currently hosts alpha nova & galerie futura’s 30-year anniversary exhibition, was blockaded with black balloons. When I arrived, Bikoro was already methodically working her way through them. Also clothed in black, slowly and with care, the artist cradled each balloon against her ear and then punctured it with a pin. With each explosion, a small amount of white powder was expelled from the balloon and onto Bikoro’s body, layers of white settling like numbness or silence. All the while, a small, hidden speaker played sections of the sound archives in which women’s voices could be heard.

Hearing loss is caused by trauma to the ear. Trauma occurs when a distressing event cannot be integrated into a narrative. The work extends Bikoro’s project to decolonialize the process of monument-making, uncovering fragmented migrant histories that have been „othered“, silenced or buried.

Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, If You Fail To Cross The Rubicon, 2016, performance

Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, If You Fail To Cross The Rubicon, 2016, performance

Photo: Joanna Kosowska

Project Space Festival Day 19: grüntaler 9

„A flailing attempt to navigate shifting terrain“ is how Johanna Gilje described her recently published book, the desire to contain and the inevitability of rupture. Perhaps this statement might be extended to her project at grüntaler 9: a nine-hour long interview conducted on a rotating basis with performance artists Ilya Noé, Teena Lange, Raegan Truax and Stephanie Maher about artistic process.

grüntaler 9 is a space for live performance and time-based art in which traces of each performance are left behind. Its distinctive checkered floor and yellow walls are stained with nails, tape, texts, and other, less recognizable marks. Those who use the space often interact with its layers of recent history, creating a palimpsest of sorts. Here, meaning is also generate between the works, a process slightly beyond control.

Collaborative meaning-making also seemed to be the focus in Johanna Gilje’s nine-hour interview marathon. Apart from its length, the interview was defined by a number of other significant features. Firstly, it was conducted in water. A small pond filled the space, and those wishing to join had first to pull on gumboots. Moreover, Gilje has developed a special process for interviews between three rotating conversation partners: The first person asks questions, the second answers, and the third „navigates“; plucking significant landmarks out of the conversation and writing them down once all three have reached consensus that the chosen word or phrase accurately represents the dialogue so far. This, as it turned out, was a way of maintaining continuity, ensuring everyone was clear on what exactly was being said.

Johanna Gilje, the desire to contain and the inevitability of rupture, 2016, durational interview

Johanna Gilje, the desire to contain and the inevitability of rupture, 2016, durational interview

Photo: Why Alix

Although I was not present for the full nine hours, I happened to walk in at the tipping point when the artists began questioning the framework. Raegan Truax observed that she could not talk without first understanding a space with her body, and proceeded to do just that, prompting an improvised physical exploration. At least some of the water in the pond was displaced, and at least one body became wet. Later, an animated conversation between Stephanie Maher and Teena Lange turned to more urgent questions of trust in grüntaler 9: what limitations should be maintained in a space where everything, in theory, is possible? What should not be allowed? What would constitute a betrayal of trust? Knocking down the walls?

While space delimits the body, which in turn delimits conversation, there is always the possibility for rupture.

Project Space Festival Day 20: Sonntag

In August, 2016, Sunday took place on Saturday. Sonntag is a particular project format in which the work of one artist is presented – together with their favorite cake – in a private space on the third Sunday of each month.

Sonntag developed into a nomadic project after Adrian Schiesser – who runs the space together with April Gertler – was not granted permission by his landlord to run the monthly event in his own apartment. Ever since that point the project has been hosted by a network of friends and acquaintances. This means that Sonntag moves from location to location – but always takes place in an apartment. Neither exhibition nor artist’s talk, Sonntag has developed its own format akin to the Art Salon. Although there is no reading or musical presentation, as was the case in the 18th and 19th centuries, a piece of cake is shared over conversation about the exhibited work of the artist. Here, the popular German tradition of „Kaffee-und-Kuchen“ overlaps with the democratized interpretation of the intellectual-cultural exchange of the Salon.

Behind this apparent lightness, April Gertler and Adrian Schiesser offer the opportunity to experience a body of artistic work in a completely different way – in a spirit of intimacy and conviviality. Rather than simply hanging the work over the sofa, this arrangement leads to interventions and installations which work with the private space. The artwork is embedded in familiar surrounds, entering into dialogue with everyday objects. In this way, the artwork moves beyond the decorative role it would typically play in a purely private home context. It retains its autonomy despite existing an intimate relationship with its surroundings.

This intimacy arises not only through its relationship to the apartment, but also, importantly, through cake: because April and Adrian accompany the presentation of the work with a self-made sample of the invited artist’s favorite cake. This is a sensory way of providing intimate access to the world of the artist, and at the same time creates a setting for heartfelt creativity, making an informal exchange between artist, visitors and work possible.

Sonntag presents Alon Levin, 2016, installation view

Sonntag presents Alon Levin, 2016, installation view

Photo: Why Alix

On Saturday, the 20th of August, Sonntag presented Alon Levin with a Red Velvet cake – a cake of sober beauty, made of two purple-red layers and covered with a white cream – the perfect metaphor for the works of the invited artist. These were, at first glance, full of elusive sobriety. If you looked closer, you would discover that Alon has connected layers of text, research, objects, painting, printmaking and autobiographical elements with humor, imagination and intelligence. His work not only directed the gaze towards the symbolic representation of concepts, such as that of the modern or „things contemporary“ (as implied by the title of one of his publications).

In the apartment, located in Wedding, two paintings of red hibiscus paintings leaned against the wall. Opposite these stood two cardboard rolls printed with further flowers, stylised and combined with symbolic forms reminiscent of encyclopedic diagrams. A supporting beam above carried a series of small flags out of ceramic, which echo colours taken from the symbolic visual language of flowers from the Victorian era. Here, in this spatial constellation, Alon Levin opened a conversation with us about the concept of beauty, its meaning and its social and political relevance.

I went back for two second servings…

Project Space Festival Day 21: centrum

Never trust a nymph, the subtitles of Madeline Stillwell’s film Prelude to Never Loving Again warned. The film consisted of a collage of footage from road construction sites, Wagner’s early opera Das Rheingold and subtitles summarizing the saga, with its three Rhine nymphs Woglinde, Wellgunde and Flosshilde, the evil dwarf Alberich, and a guest appearance from Wagner „him“self. All roles were played by the artist, sprawled across the film in a lo-fi greenscreen effect, a moving, orgiastic sculpture of construction site debris: buckets, bricks, pipes, wires, bits of plastic and clay smeared liberally everywhere. As the drama played out, the nymphs, exuding touch-me-not libidinal energy, simultaneously flirted with Alberich and guarded their precious Rhinegold, while Alberich’s desparation for lusty action eventually turned into greed, and he stole the Rhinegold. Enter the artist in his self-satisfaction: a bearded Wagner, revelling in his Gesamtkunstwerk with a mastabatory pot of clay.

Madeline Stillwell, Prelude to Never Loving Again, 2016, digital video

Madeline Stillwell, Prelude to Never Loving Again, 2016, digital video

Photo: Why Alix

Maybe it was about love, maybe it was about art, maybe it was about the monumental Gesamtkunstwerk of the city, maybe it was about fantasies of total control. One thing was for sure: all the rubbish will come back to haunt you in the end and create an ecstasy all of its own.